Since Grandpa liked to turn bowls and plates for household use and gifts, it was a natural step for me to start turning bowls. At first my bowls were turned from pine under his watchful eye. To get the needed swing to turn a bowl, he had reworked the old lathe so that a faceplate and tool rest could be used on the back side of the spindle. Later, after Grandpa had passed and the Boss and I were married, we gathered oak millwork scrap ends from her father's workplace. We glued these scraps into bowl sized chunks and turned bowls using the reworked lathe. Yes, I said we. The Boss was a wood turner long before she became a glass stacker. Several of the oak bowls that we created in the '70s are in use or on display in our home.

|

| Bowl, Red Oak, The Boss, 1975 |

During the early years of our marriage I built a lathe for myself using angle iron and a rectangular tubing frame with a solid spindle mounted on a wooden table. It worked well enough but always had vibration and stability issues. I still use it for sanding and light turning but have recently purchased a well used 1922 Oliver 51-A-42 for most of my turning.

Not too long ago, the Boss and I spent part of the winter at The Resort in Mesa, Arizona. After moving in we found that the park had a very well equipped wood shop for resident use. The shop had two Jet lathes! It was like falling off the pier and landing in chocolate pudding. I was about to be turning on a professional lathe!

While we were in Arizona that winter, I did not have access to a wood pile or a millwork shop to provide a free source of scraps for turning. Lumber had to be purchased. To use less material, I decided to make stave bowls. I also wanted to make bowls with a prime number of segments. There was some geometry, trigonometry and a healthy dose of algebra stored in the back of my head and I just mixed that all up and fed it into the solve function of my HP 48G. Now I have the program to quickly and exactly determine the stave length, taper, and miter angle for any sized bowl.

Calculating the numbers is only part of the operation. Next, the staves must each be accurately and consistently cut. A set of jigs are used to hold the stave while it is fed through the table saw in a series of cuts to reach its final shape and size.

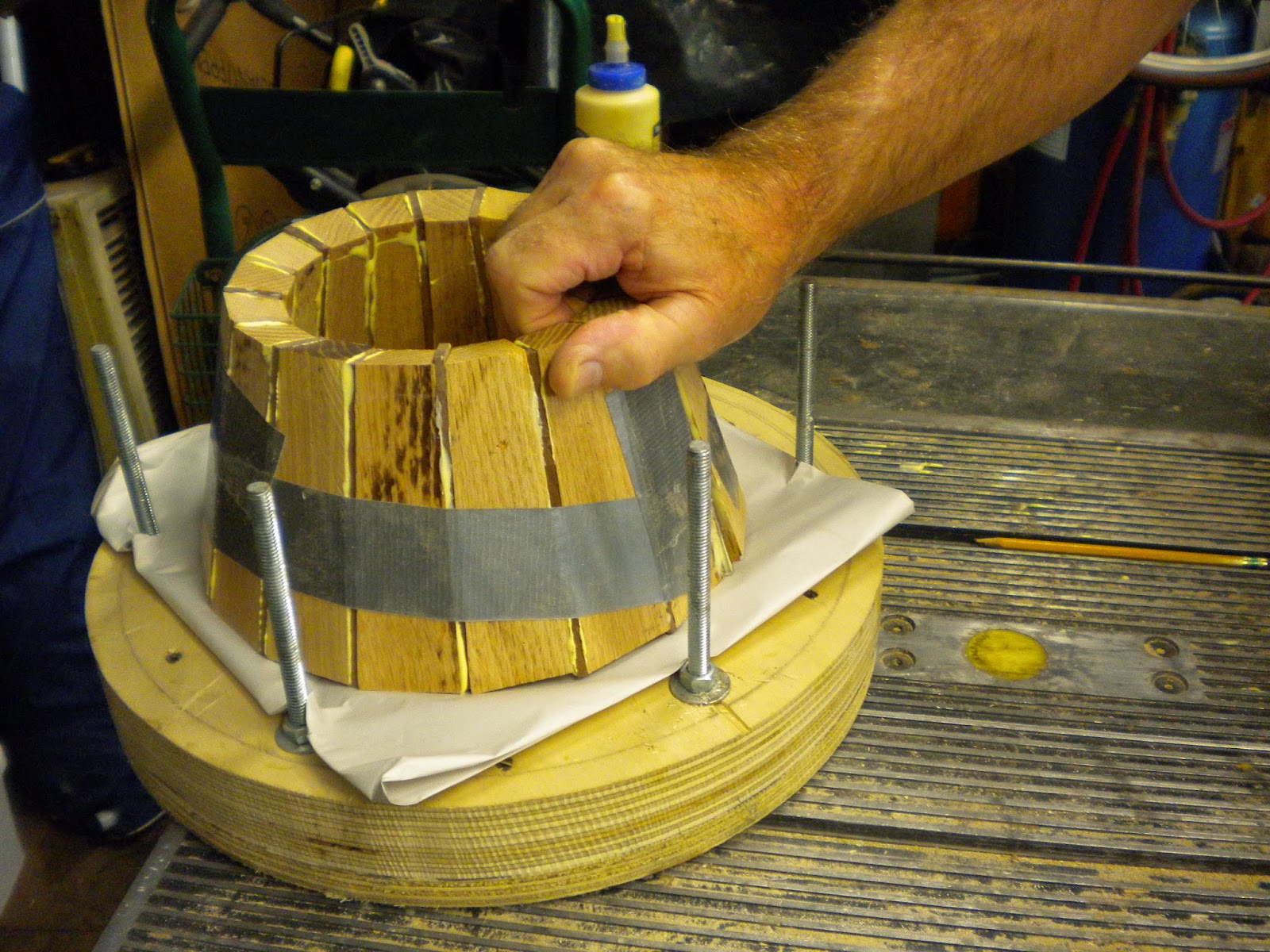

The cut staves are then assembled and glued into a bowl blank using another jig. This fixture is large enough to hold a bowl and has a socket for a faceplate on its backside so it can be placed on the lathe. The bowl pictured below has 17 red oak staves with black walnut spacers.

Bowl bottoms are made, fitted and glued in place using the fixture.

Bowls are turned to a rough shape. Then they are sanded to #2000 in steps, starting with #36. Last, they are finished using light rubbings with very fine steel wool between each of four coats of butcher block oil.

|

| A finished bowl, Red Oak and Black Walnut, November, 2014 |

I made two discoveries that winter in Mesa. After purchasing several pieces of mesquite at a local woodworking store I found it to be an excellent turning wood; it is a hardwood with great finishing properties and very interesting color. This winter I plan to visit a mesquite sawmill near Tumacacori, Arizona and purchase about 15 board feet of mesquite, enough for about 10 segmented bowls.

|

| Bowl, Mesquite and Black Walnut, 2013 |

| Bowl, Baltic Birch Plywood, 2013 |

keep 'em running

As always

the GlassStacker's Assistant

No comments:

Post a Comment